Resilience Training for Educators

By Martin Seligman, Ph.D.

By Martin Seligman, Ph.D.

What is positive education?

“Positive education is defined as education for both traditional skills and for happiness. The high prevalence worldwide of depression among young people, the small rise in life satisfaction, and the synergy between learning and positive emotion all argue that the skills for happiness should be taught in school. There is substantial evidence from well controlled studies that skills that increase resilience, positive emotion, engagement and meaning can be taught to schoolchildren.” From Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions by Martin E.P. Seligman, Randal M. Ernst, Jane Gillham, Karen Reivich, and Mark Linkins

Teaching Well-Being in Schools

The following is an excerpt from Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being

First, a quiz:

Question one: in one or two words, what do you most want for your children?

If you are like the thousands of parents I’ve polled you responded, “Happiness,” “Confidence,” “Contentment,” “Fulfillment,” “Balance,” “Good stuff,” “Kindness,” “Health,” “Satisfaction,” “Love,” “Being civilized,” “Meaning,” and the like. In short, well-being is your topmost priority for your children.

Question two: in one or two words, what do schools teach?

If you are like other parents, you responded, “Achievement,” “Thinking skills,” “Success,” “Conformity,” “Literacy,” “Math,” “Work,” “Test taking,” “Discipline,” and the like. In short, what schools teach is how to succeed in the workplace.

Notice that there is almost no overlap between the two lists.

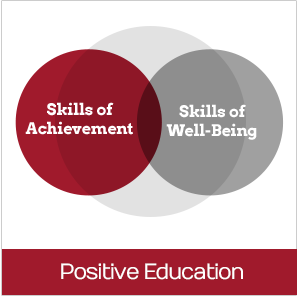

The schooling of children has, for more than a century, paved the boulevard toward adult work. I am all for success, literacy, perseverance, and discipline, but I want you to imagine that schools could, without compromising either, teach both the skills of well-being and the skills of achievement. I want you to imagine positive education.

Should well-being be taught in schools?

The prevalence of depression among young people is shockingly high worldwide. By some estimates, depression is about ten times more common now than it was fifty years ago. This is not an artifact of greater awareness of depression as a mental illness, since much of the data arises from door to door surveys which ask tens of thousands of people “did you ever try to kill yourself?,” “did you ever cry every day for two weeks?,” and the like without ever mentioning depression. Depression now ravages teenagers: fifty years ago, the average age of first onset was about thirty. Now the first onset is below age fifteen.

There is much more depression, affecting those much younger, and average national happiness—which has been measured competently for a half century—has not remotely kept up with how much better the objective world has become. Happiness has gone up only spottily, if at all. The average Dane, Italian, and Mexican is somewhat more satisfied with life than fifty years ago, but the average American, Japanese, and Australian is no more satisfied with life than fifty years ago, and the average Brit and German is less satisfied. The average Russian is much unhappier.

Two good reasons that well-being should be taught in schools are the current flood of depression and the nominal increase in happiness over the last two generations. A third good reason is that greater well-being enhances learning, the traditional goal of education. Positive mood produces broader attention, more creative thinking, and more holistic thinking. This, in contrast to negative mood, which produces narrowed attention, more critical thinking, and more analytic thinking. When you’re in a bad mood, you’re better at “what’s wrong here?” When you’re in a good mood, you’re better at “what’s right here?” Even worse: when you are in a bad mood, you fall back defensively on what you already know, and you follow orders well. Both positive and negative ways of thinking are important in the right situation, but all too often schools emphasize critical thinking and following orders rather than creative thinking and learning new stuff. The result is that children rank the appeal of going to school just slightly above going to the dentist. In the modern world, I believe we have finally arrived at an era in which more creative thinking, less rote following of orders—and yes, even more enjoyment—will succeed better.

I conclude that, were it possible, well-being should be taught in school because it would be an antidote to the runaway incidence of depression, a way to increase life satisfaction, and an aid to better learning and more creative thinking.

Can well-being be taught in schools?

My research team, led by Karen Reivich and Jane Gillham, has devoted much of the last twenty years to finding out, using rigorous methods, whether well-being can be taught to school children. We believe that well-being programs, like any medical intervention, must be evidence based, so we have tested two different programs for schools: the Penn Resiliency Program (PRP), and the Strath Haven Positive Psychology Curriculum. Here are our findings.

The Penn Resiliency Program

First, let me tell you about the Penn Resiliency Program: its major goal is to increase students’ ability to handle day-to-day problems that are common during adolescence. PRP promotes optimism by teaching students to think more realistically and flexibly about the problems they encounter. PRP also teaches assertiveness, creative brainstorming, decision making, relaxation, and several other coping skills. PRP is the most widely researched depression-prevention program in the world. During the past two decades, twenty-one studies have evaluated PRP in comparison to control groups. Many of these studies used randomized controlled designs. Together these studies include more than three thousand children and adolescents between the ages of eight and twenty-two. Here are the basic findings:

- Penn Resiliency Program reduces and prevents symptoms of depression.

- Penn Resiliency Program reduces hopelessness. The meta-analysis also found that PRP significantly reduced hopelessness, increased optimism, and increased well-being.

- Penn Resiliency Program prevents clinical levels of depression and anxiety.

- Penn Resiliency Program reduces and prevents anxiety.

- Penn Resiliency Program reduces conduct problems.

- PRP works equally well for children of different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

- Penn Resiliency Program improves health-related behaviors, with young adults who complete the program having fewer symptoms of physical illness, fewer illness doctor visits, better diet and more exercise.

- Training and supervision of group leaders is critical.

- The fidelity of curriculum delivery is critical.

The Strath Haven Positive Psychology Curriculum

So the Penn Resiliency Program reliably prevents depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in young people. Resilience, however, is only one aspect of positive psychology; the emotional aspect. We designed a more comprehensive curriculum that builds character strengths, relationships, and meaning, as well as raises positive emotion and reduces negative emotion. With a $2.8 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education, we carried out a large randomized, controlled evaluation of this high school positive psychology curriculum. At Strath Haven High School, outside of Philadelphia, we randomly assigned 347 ninth-grade students (fourteen- to fifteen-year-olds) to language arts classes. Half the classes incorporated the positive psychology curriculum; the other half did not. Students, their parents, and teachers completed standard questionnaires before the program, after the program, and over two years of follow-up. We tested students’ strengths (for instance, love of learning, kindness), social skills, behavioral problems, and how much they enjoyed school. In addition, we looked at their grades.

The major goals of this global program are (1) to help students identify their signature character strengths and (2) to increase their using these strengths in their daily lives. In addition to these goals, the intervention strives to promote resilience, positive emotion, meaning and purpose, and positive social relationships. The curriculum consists of more than twenty eighty-minute sessions delivered over the ninth-grade year. These involve discussing character strengths and the other positive psychology concepts and skills, a weekly in-class activity, real-world homework in which students apply these skills in their own lives, and journal reflections.

Here are two examples of the exercises we use in the curriculum:

Three-Good-Things Exercise

We instruct the students to write down daily three good things that happened each day for a week. The three things can be small in importance (“I answered a really hard question right in language arts today”) or big (“The guy I’ve liked for months asked me out!!!”). Next to each positive event, they write about one of the following: “Why did this good thing happen?” “What does this mean to you?” “How can you have more of this good thing in the future?”

Using Signature Strengths in New Ways

Honesty. Loyalty. Perseverance. Creativity. Kindness. Wisdom. Courage. Fairness. These and sixteen other character strengths are valued in every culture in the world. We believe that you can get more satisfaction out of life if you identify which of these character strengths you have in abundance and then use them as much as possible in school, in hobbies, and with friends and family.

Students take the Values in Action Signature Strengths test (go to Test Center) and use their highest strength in a new way at school in the next week. Several sessions in the curriculum focus on identifying character strengths in themselves, their friends, and the literary figures they read about, and using those strengths to overcome challenges.

Here are the basic findings of the positive psychology program U.S. Department of Education program at Strath Haven:

Engagement in learning, enjoyment of school, and achievement

The positive psychology program improved the strengths of curiosity, love of learning, and creativity, by the reports of teachers who did not know whether the students were in the positive psychology group or the control group. (That’s what is called a “blind” study because the raters do not know the status of the students they are rating.) The program also increased students’ enjoyment and engagement in school. This was particularly strong for regular (nonhonors) classes, in which positive psychology increased students’ language arts grades and writing skills through eleventh grade. In the honors classes, grade inflation prevails and almost all students get As, so there is too little room for improvement. Importantly, increasing well-being did not undermine the traditional goals of classroom learning; rather it enhanced them.

Social skills and conduct problems

The positive psychology program improved social skills (empathy, cooperation, assertiveness, self-control), according to both mothers’ and “blind” teachers’ reports. The program reduced bad conduct, according to mothers’ reports.

The Geelong Grammar School Project

Is it possible that an entire school can be imbued with positive psychology?

In January 2008, Karen and I and fifteen of our Penn trainers (mostly MAPP graduates) flew to Australia to teach one hundred members of the Geelong Grammar faculty. In a nine-day course, we first taught the teachers to use the skills in their own lives—personally and professionally—and then we gave examples and detailed curricula of how to teach them to children. The principles and skills were taught in plenary sessions, and reinforced through exercises and applications in groups of thirty, as well as in pairs and small groups.

Following the training, several of us were in residence for the entire year, and about a dozen visiting scholars came, each for a week or more, to instruct faculty in their positive psychology specialties. Here’s what we devised, which essentially divides into “Teaching it,” “Embedding it,” and “Living it.”

Teaching It: Stand-alone courses and course units are now taught in several grades to teach the elements of positive psychology: resilience, gratitude, strengths, meaning, flow, positive relationships, and positive emotion.

Embedding It: Geelong Grammar teachers embed positive education into academic courses, on the sports field, in pastoral counseling, in music, and in the chapel. For example: English teachers use signature strengths and resiliency to discuss novels; Religion teachers ask students about the relationship between ethics and pleasure; Music teachers use resilience skills to build optimism from performances that did not go well. Athletic coaches teach the skill of “letting go of grudges” against teammates who perform poorly. Chapel is another locus of positive education. Scriptural passages on courage, forgiveness, persistence, and nearly every other strength are referenced during the daily services, reinforcing current classroom discussions.

Living It: Like all Geelong Grammar six-year-olds, Kevin starts his day in a semicircle with his uniformed first-grade classmates. Facing his teacher, Kevin’s hand shoots up when the class is asked, “Children, what went well last night?” Eager to answer, several first graders share brief anecdotes such as “We had my favorite last night: spaghetti” and “I played checkers with my older brother, and I won.” Kevin says, “My sister and I cleaned the patio after dinner, and Mum hugged us after we finished.” The teacher follows up with Kevin. “Why is it important to share what went well?” He doesn’t hesitate: “It makes me feel good.” “Anything more, Kevin?” “Oh, yes, my mum asks me what went well when I get home every day, and it makes her happy when I tell her. And when Mum’s happy, everybody’s happy.”

Positive education at Geelong Grammar School is a work in progress and is not a controlled experiment. Melbourne Grammar School up the road did not volunteer to be a control group. So I cannot do better than relate before-and-after stories. But the change is palpable, and it transcends statistics. The school is not frowny anymore. I was back again for a month in 2009, and I have never been in a school with such high morale. I hated to leave and return to my own frowny university. Not one of the two hundred faculty members left Geelong Grammar at the end of the school year. Admissions, applications, and donations are way up.

A New Prosperity

Prosperity-as-usual has been equated with wealth. Based on this formulation, it is commonly said in the rich nations that this may be the last generation to do better than its parents. That may be true of money, but is it more money that every parent wants his children to have? I don’t believe so. I believe that what every parent wants for their children is more well-being than they themselves had. By this measure, there is every hope that our children will do better than their parents.

The time has come for a new prosperity, one that takes flourishing seriously as the goal of education and of parenting. Learning to value and to attain flourishing must start early—in the formative years of schooling—and it is this new prosperity, kindled by positive education, that the world can now choose.

Learn More About Positive Education

Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being: Read chapters 4 (“Teaching Well-Being: The Magic of MAPP”), 5 (“Positive Education: Teaching Well-Being to Young People”) and 6 (“GRIT, Character, and Achievement: A New Theory of Intelligence”).

Research on Resilience/Positive Education

Seligman, M.E.P., Ernst, R.M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education (35) 3, 293-311.