Positive Health

Also check out the Positive Health website!

What is Positive Health?

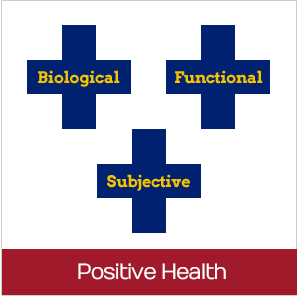

The field of medicine has long focused on the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and cure of disease. But health is more than the mere absence of disease. The emerging concept of Positive Health takes an innovative approach to health and well-being that focuses on promoting people’s positive health assets—strengths that can contribute to a healthier, longer life. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Pioneer Portfolio is funding research to help identify these assets, which might include biological factors, such as high heart rate variability; subjective factors, such as optimism; and functional factors, such as a stable marriage. This research has implications for prevention, health promotion, public health and medicine.

The field of medicine has long focused on the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and cure of disease. But health is more than the mere absence of disease. The emerging concept of Positive Health takes an innovative approach to health and well-being that focuses on promoting people’s positive health assets—strengths that can contribute to a healthier, longer life. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Pioneer Portfolio is funding research to help identify these assets, which might include biological factors, such as high heart rate variability; subjective factors, such as optimism; and functional factors, such as a stable marriage. This research has implications for prevention, health promotion, public health and medicine.

According to Martin Seligman, PhD, project director and director of the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, Positive Health encompasses the understanding that "people desire well-being in its own right and they desire it above and beyond the relief of their suffering." Seligman and a team of researchers are working to identify potential health assets and see if they may reveal a variety of potent, low-cost approaches to enhance well-being and help protect against physical and mental illness. If health assets can be scientifically linked to positive health outcomes, the ultimate goal would be to design interventions that can help build and sustain these assets to help people increase their chances of living a healthier, longer life.

“The definition of positive health is empirical, and we are investigating the extent to which these three classes of assets actually improve the following health and illness targets:

- Does positive health extend lifespan?

- Does positive health lower morbidity?

- Is health care expenditure lower for people with positive health?

- Is there better mental health and less mental illness?

- Do people in positive health not only live longer but have more years in good health?

- Do people in positive health have a better prognosis when illness finally strikes?

So the definition of positive health is the group of subjective, biological, and functional assets that actually increase health and illness targets.”

- Martin E.P. Seligman, from Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being

The Positive Health Initiative

The positive health initiative is supported by a $2.8 million grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Re-analysis of Existing Longitudinal Studies

We started by reanalyzing six large long term studies of predictors of illness—studies that originally focused on risk factors, not on health assets. This project is led by Dr. Laura Kubzansky, Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences in the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Kubzansky reanalyzes cardiovascular disease risk for its psychological underpinnings, we have asked if these studies, reanalyzed for assets, predict the health targets above. While the existing data sets concentrate on the negative, these six contain more than a few snippets of the positive, which until now have been largely ignored. So, for example, some of the tests ask about levels of happiness, exemplary blood pressure, and marital satisfaction. Our work examines what configuration of positive subjective, biological, and functional measures emerge as health assets. This committee includes Dr. Julia Boehm, Dr. Nansook Park, and Eric Kim. It should also be noted that Dr. Chris Peterson, Professor of Psychology, University of Michigan, co-led this project and made many important contributions to the science of positive health before his death in 2012.

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

In the mid-1980s, 120 men from San Francisco had their first heart attacks, and they served as the untreated control group in the massive Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (acronymic MR FIT) study. This study disappointed many psychologists and cardiologists by ultimately finding no effect on CVD by training to change these men’s personalities from type A (aggressive, time urgent, and hostile) to type B (easygoing). The 120 untreated controls, however, were of great interest to Gregory Buchanan, then a graduate student at Penn, and to me because so much was known about their first heart attacks: extent of damage to the heart, blood pressure, cholesterol, body mass, and lifestyle—all the traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease. In addition, the men were all interviewed about their lives: family, job, and hobbies. We took every single “because” statement from each of their videotaped interviews and coded it for optimism and pessimism.

Within eight and a half years, half the men had died of a second heart attack, and we opened the sealed envelope. Could we predict who would have a second heart attack? None of the usual risk factors predicted death: not blood pressure, not cholesterol, not even how extensive the damage from the first heart attack. Only optimism, eight and a half years earlier, predicted a second heart attack: of the sixteen most pessimistic men, fifteen died. Of the sixteen most optimistic men, only five died.

All studies of optimism and CVD converge on the conclusion that optimism is strongly related to protection from cardiovascular disease. This holds even correcting for all the traditional risk factors such as obesity, smoking, excessive alcohol use, high cholesterol, and hypertension. It even holds correcting for depression, correcting for perceived stress, and correcting for momentary positive emotions. It holds over different ways of measuring optimism. Most importantly, the effect is bipolar, with high optimism protecting people compared to the average level of optimism and pessimism, and pessimism hurting people compared to the average.

Cardiovascular Health Assets

Is there a set of subjective, biological, and functional assets that will boost your resistance to cardiovascular disease beyond average? Is there a set of subjective, biological, and functional assets that will improve your prognosis beyond average if you should have a heart attack? This vital question is largely ignored in CVD research, which focuses on the toxic weaknesses that decrease resistance or undermine prognosis once a first heart attack occurs. The beneficial effect of optimism as a health asset on CVD is a good start, and the aim of our Cardiovascular Health Committee is to broaden our knowledge of health assets. The committee is headed by Dr. Darwin Labarthe, Professor in Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; former director of cardiovascular epidemiology at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

Exercise as a Health Asset

Just as optimism is a subjective health asset for cardiovascular disease, it is clear that exercise is a functional health asset: people who exercise a moderate amount have increased health and low mortality, while couch potatoes have poor health and high mortality. The beneficial effects of exercise on health and illness are finally well accepted even within the most reductionist part of the medical community, a guild very resistant to any treatment that is not a pill or a cut. The surgeon general’s 2008 report enshrines the need for adults to do the equivalent of walking 10,000 steps per day. (The real danger point is fewer than 5,000 steps a day, and if this describes you, I want to emphasize that the findings that you are at undue risk for death are—there is no other word for it—compelling.) To take the equivalent of 10,000 steps a day can be done by swimming, running, dancing, weight lifting; even yoga and a host of other ways of moving vigorously.

Fitness Versus Fatness

The United States has a great deal of obesity, enough so that many call it an epidemic, and huge resources are expended by the government and by private foundations, Robert Wood Johnson included, to curtail this epidemic. Obesity is undeniably a cause of diabetes, and on that ground alone, measures to make Americans less fat are warranted. However, Dr. Steve Blair, Professor in Exercise Science, University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health, believes that the real epidemic, the worst killer, is the epidemic of inactivity, and his argument is not lightweight. Here is the argument:

Poor physical fitness correlates strongly with all-cause mortality, and particularly with cardiovascular disease. Lack of exercise and obesity go hand in hand. Fat people don’t move around much, whereas thin people are usually on the go. So which of these two—obesity or inactivity—is the real killer?

There is a huge literature that shows that fat people die of cardiovascular disease more than thin people, and this literature is careful, adjusting for smoking, alcohol, blood pressure, cholesterol, and the like. Very little of it, unfortunately, adjusts for exercise. But Steve’s many studies do. These data show the risk for death in normal-weight versus obese people who are fit or unfit. In the unfit groups, normal and obese people both have a high risk for death, and it does not seem to matter if you are fat or thin. In the fit groups, both fat and thin people have a much lower risk of death than their counterparts in the unfit groups, with fat, but fit people at only slightly more risk than thin fit people. But what I now emphasize is that fat people who are fit have a low risk of death.

Steve concludes that a major part of the obesity epidemic is really a couch potato epidemic. Fatness contributes to mortality, but so does lack of exercise. There are not enough data to say which contributes more, but they are compelling enough to require that all future studies of obesity and death adjust carefully for exercise.

Measurement of Well-Being

The primary goal of the Psychological Well-Being Measurement Committee is to devise measures of psychological well-being that can be used in health and medicine. Although measures of psychological problems are used in medicine, for example symptom inventories that measure depression, the goal of the Psychological Well-Being Measurement Committee is to broaden the psychological measures to include positive psychological well-being factors such as life satisfaction, positive feelings, social support, and purpose in life. We will include psychological variables in our measures that have been shown in existing research to be associated with physical and mental health. We envision creating several measures of psychological well-being, both brief and longer, that could be used by medical practitioners for screening, as well as measures that would be more detailed and could be used in research settings and when more depth is needed, for example in health-counseling settings. A secondary goal of the committee is to create a core of measures that can be used in national samples for policy purposes. The committee is chaired by Dr. Ed Diener, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, University of Illinois; Senior Scientist for the Gallup Organization. The committee includes Dr. John Helliwell, Dr. Richard Lucas, Dr. Louis Tay, Dr. Rong Su, and ex-officio members Dr. Darwin Labarthe, and Dr. Martin E.P. Seligman.

Adolescent Positive Health

Among social and behavioral scientists who study adolescence - roughly defined as the second decade of life - it is widely agreed that positive health during adolescence entails more than the mere absence of illness or behavioral problems. Although as parents, educators, and health practitioners we certainly hope that young people emerge from adolescence completing high school and being free from illness, disability, substance abuse problems, criminal activity, or premature parenthood, we want and expect more than this minimum. We want our teenagers to be healthy and vibrant, not merely free of disease; optimistic and exuberant, not simply "non-depressed"; intimately connected to others, not just part of the crowd; intellectually curious and determined to succeed in academic and extracurricular pursuits, not simply content to do just what it takes to avoid failing; and passionately engaged in activities that excite them, not just "occupied." What does it mean to "flourish" during adolescence? Our intent is to define it, understand it, measure it, and see how well it predicts future psychological and physical well-being. The committee is chaired by Dr. Laurence Steinberg, Professor of Psychology, Temple University. The committee includes: Dr. Margaret Kern, Dr. Christopher Forrest, Dr. Katherine Bevans, Elizabeth Steinberg, and Lizbeth Benson.

Learn More About Positive Health

Flourish: A Visionary Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being Chapter 9 (“Positive Physical Health: The Biology of Optimism”).

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation – Grant Page

Dr. Seligman's article on positive health in Applied Psychology: An International Review

Press Articles

Re-analysis of Existing Studies

ABC News: Attitude Adjustment: Optimism Can Stave Off Stroke in Older Patients

USA Today: Optimism may lower stroke risk

The Atlantic: Liking your neighbors could help prevent you from having a stroke

Huffington Post:Good cholesterol affected by middle-aged optimism, new study finds

International Business Times: Eat your way to happiness with fruit and veg

BBC News: Being an optimist may protect against heart problems

Huffington Post: Optimism could be the secret to a healthy heart, study suggests

US News and World Report: Optimism might cut your risk for heart attack

CBS News: Optimism protects against heart attack and stroke, study shows

ABC News: Can optimism ward off heart ills?

The Telegraph: Positive outlook on life linked to lower risk of heart attacks: research

US News and World Report: Take action for heart health

The Atlantic: What we know now about how to be happy

New York Times: Really? Optimism reduces the risk of heart disease

Time: A happy, optimistic outlook may protect your heart

Cardiovascular Health

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Blog: A quiet revolution in cardiovascular health

Academic Publications

Re-analysis of Existing Studies

Kim, E.S., Park, N., Peterson, C. (in press). Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and stroke. Social Science & Medicine.

Kim, E.S., *Sun, J.K., Park, N., Peterson, C. (2013). Purpose in life and reduced stroke in older adults: The Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 74(5), 427-432.

Kim, E.S., Park, N., Peterson, C. (2011). Dispositional optimism protects older adults from stroke: The Health and Retirement Study. Stroke, 42(10), 2855 -2859.

Kim, E.S., *Sun, J.K., Kubzansky, L.D., Park, N., Peterson, C. (2013). Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older U.S. adults with coronary heart disease: A two-year follow-up. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(2), 124-133.

Peterson, C., Park, N., Kim, E.S. (2012). Can optimism decrease risk of illness and disease among the elderly? Aging Health, 8(1), 5-8.

Boehm, J. K., Williams, D. R., Rimm, E. B., Ryff, C., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2013). Relation between optimism and lipids in midlife. American Journal of Cardiology, 111, 1425-1431.

Boehm, J. K., Williams, D. R., Rimm, E. B., Ryff, C., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2013). Association between optimism and serum antioxidants in the Midlife in the United States study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75, 2-10.

Boehm, J. K., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2012). The heart’s content: The association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 655-691.

Boehm, J. K., Vie, L. L., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2012). The promise of well-being interventions for improving health risk behaviors. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports, 6, 511-519.

Boehm, J. K., Peterson, C., Kivimaki, M., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2011). Heart health when life is satisfying: Evidence from the Whitehall II cohort study. European Heart Journal, 32, 2672-2677.

Boehm, J. K., Peterson, C., Kivimaki, M., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2011). A prospective study of positive psychological well-being and coronary heart disease. Health Psychology, 30, 259-267.

Appleton AA, Buka SL, Loucks EB, Gilman SE, Kubzansky LD. Divergent associations of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies with inflammation. Health Psychology. 32(7): 748-756, 2013

Cardiovascular Health

Labarthe DR. From cardiovascular disease to cardiovascular health: A quiet revolution? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:e86-e92.

Shay, C. M., Ning, H., Daniels, S. R., Rooks, C. R., Gidding, S. S., & Lloyd-Jones, D. M. (2013). Status of Cardiovascular Health in US Adolescents: Prevalence Estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005-2010. Circulation.

Exercise

Haskell, W. L., Blair, S. N., & Hill, J. O. (2009). Physical activity: health outcomes and importance for public health policy. Preventive medicine, 49(4), 280-282.

Weiler, R., Stamatakis, E., & Blair, S. (2010). Should health policy focus on physical activity rather than obesity? Yes. BMJ, 340.

Warren, T. Y., Barry, V., Hooker, S. P., Sui, X., Church, T. S., & Blair, S. N. (2010). Sedentary behaviors increase risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 42(5), 879.

Mitchell, J. A., Bornstein, D. B., Sui, X., Hooker, S. P., Church, T. S., Lee, C. D., & Blair, S. N. (2010). The impact of combined health factors on cardiovascular disease mortality. American heart journal, 160(1), 102-108.

Byun, W., Sieverdes, J. C., Sui, X., Hooker, S. P., Lee, C. D., Church, T. S., & Blair, S. N. (2010). Effect of positive health factors and all-cause mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 42(9), 1632-8.

Ortega, F. B., Lee, D. C., Sui, X., Kubzansky, L. D., Ruiz, J. R., Baruth, M., & Blair, S. N. (2010). Psychological well-being, cardiorespiratory fitness, and long-term survival. American journal of preventive medicine, 39(5), 440-448.

Church, T. S., Blair, S. N., Cocreham, S., Johannsen, N., Johnson, W., Kramer, K., ... & Earnest, C. P. (2010). Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association, 304(20), 2253-2262.

Measurement

Tay, L., Chan, D., & Diener, E. The Metrics of Societal Happiness. Social Indicators Research, 1-24.

Diener, E. (2012). New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. American Psychologist, 67(8), 590-597. doi: 10.1037/a0029541

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., Tay, L. (2012). Theory and validity of life satisfaction measures. Social Indicators Research, online first. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0076-y

Tay, L., Tan, K., Diener, E., & Gonzalez, E. (2012). Social relations, health behaviors, and health outcomes: A survey and synthesis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, online first. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12000

Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 1-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x